Specialization on Agile Teams

Increasing Lead Times and a Risk to Flow

01 Jun 2020 . leadership . Comments #coaching #agile development

It’s been nineteen years since the creation of the agile manifesto, and with it came the popularization of the idea that teams should be organized cross-functionally. These cross-functional teams work together on solutions rather than being organized by function, relying on handoffs between organizational silos. While a lot of progress has been made on organization and team design, I still see a lot of companies struggling with issues stemming from an overreliance on specialized teams and specialist team members.

Specialization and Solo Work

The problems with specialization within teams is compounded when teams (or their organizations) rely exclusively on solo work. Teams of specialists who don’t collaborate on work create single points-of-failure and bottlenecks in development. One person getting sick or taking a vacation interrupts team flow making it harder to deliver consistently. How often have you seen user stories or features get started and then shelved because the expert is taking a vacation? This is a common indicator of over-specialization and solo work.

Flow and Delivery Consistency

Teams trying to achieve delivery consistency, whether they are focusing on flow and continuous delivery, or still relying on story point estimates and velocity, will struggle when only certain user stories can be routed to specific team members. Teams made up of specialists that still use story points embark on the fool’s errand to track individual velocity to populate sprints with work. Instead of doubling down on story points and focusing on the individual rather than the team as the atomic unit of delivery, their time would be better spent finding ways to collaborate on the work to improve flow.

Collaboration

Collaboration is often misunderstood by those who have never truly experienced it on a development team (which is a topic for a future post). Holding team stand-ups and attending the same team meetings may be a place to start, but it isn’t sufficient. When I talk about collaboration I mean teammates working together on a shared solution, this means group design sessions, pair programming, and mob programming.

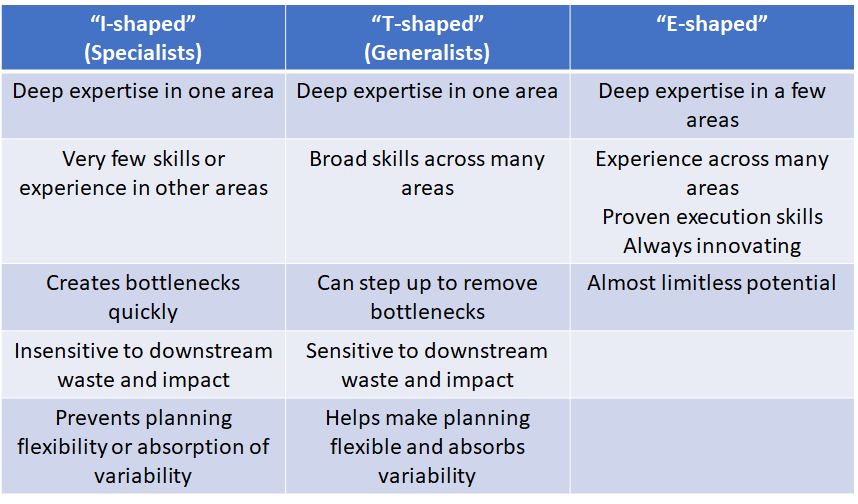

Collaborative software development techniques and an organizational culture that prioritizes learning are required to move specialists from I-Shaped to T-Shaped and eventually E-Shaped individuals. Today’s development teams are best suited by being populated by people who have deep expertise in a few key areas but are generalists in the other areas and activities necessary to continuously deliver working software.

From I-Shaped to E-Shaped Developers

The DevOps Handbook describes the importance of enabling every team member to become a generalist:

When departments over-specialize, it causes siloization…Any complex operational activity then requires multiple handoffs and queues between the different areas of the infrastructure, leading to longer lead times.

—Gene Kim, Jez Humble, Patrick Debois, & John Willis, The DevOps Handbook, page 85.

The accompanying table from The DevOps Handbook describes the important shift from specialist, to generalist and finally E-Shaped team members.

Specialized Teams

It’s an even greater challenge to an organization’s delivery capabilities when they staff teams of specialists, often returning to teams organized by function or specialty. With the rise of front-end, cloud, and infrastructure technologies the antipattern of organizing around these technologies is common. This results in the problems that cross-functional agile teams were intended to mitigate.

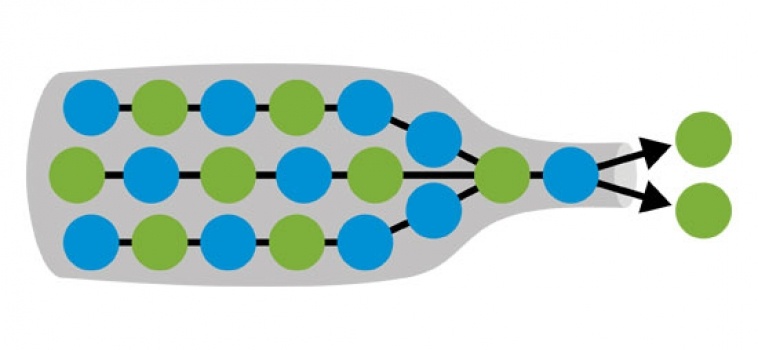

Once organized by function this creates a system where feature development requires handoffs between several teams. Organizing this way slows development to a crawl, increases lead times, and creates quality issues. Quality often suffers when handoffs are required as every handoff introduces an opportunity for mistakes, miscommunication, and defects.

A Real World Example

I once worked at a company that was beginning a large project for a new product offering. It was decided that there would be back-end teams in the local office while the front-end work would be offshored. The argument was that front-end technology stacks have become so complicated the only way to be successful was to have separate front-end and back-end teams.

This resulted in a disastrous waterfall project. The offshore front-end team was several weeks and even months ahead of other teams, they were busy building experiences against mock APIs. When the back-end onshore teams caught up, rework was required as the front-end and back-end didn’t align. “User stories” were claimed to be “Done” but delivered no customer value. In fact “completed” work wasn’t being deployed to production because it still needed to be integrated. All of this partially done work created integration risk and required waterfall testing strategies like an integrated test phase at the end of the project.

The result was a massive, year-long waterfall project in an organization that believed it was agile because they were following the Scrum events. Because it took the better part of a year to get any feedback, it was an extremely expensive bet that eschewed all of the benefits of consistently delivering working software, fast feedback cycles, and tuning the solution to meet the customers’ needs.

Cross-functional or Full Stack?

A key misunderstanding of specialization is conflating cross-functional teams with full-stack developers. A cross-functional team doesn’t require all full-stack developers. The cross-functional team consists of all skills necessary to deliver a feature from concept to production. Finding only full-stack experts as front-end and cloud technologies have emerged is a challenging proposition. This doesn’t mean specialists should be avoided, but care needs to be taken when creating development teams. Specialists should be teamed with generalists and there should be a concerted focus on collaborative development behaviors. Hire specialists, but optimize for collaboration and a path towards the emergence of E-shaped team members.

Specialists can exist on high-performing agile teams. But it is the multi-skilled team members who allow that to be possible.

—Mike Cohn - Cross-functional Doesn’t Mean Everyone Can Do Everything

A Place for Specialized Teams?

While I recommend not creating teams of specialists by function (e.g, front-end, back-end, middleware, infrastructure, database, etc.) there is a place for specialized teams. When organizing teams for fast flow you may find that there is a specific function of your software that is so specialized that it cannot be accomplished by generalists. The book Team Topologies: Organizing Business and Technology Teams for Fast Flow refers to these teams as Complicated-Subsystem teams. Some examples of complicated subsystems could include a video processing codec, a mathematical model, a real-time trade reconciliation algorithm, or a face-recognition engine.1

To learn more about this concept I highly recommend reading Team Topologies. In addition to Complicated-Subsystem teams the book describes the other three types of teams required for the fast flow of features in a software organization. Not surprisingly, the largest percentage of teams are the generalized, value stream-aligned teams. The other team types exist to support the stream-aligned teams, who are responsible for delivering the lion’s share of customer value in an organization.

A complicated-subsystem team is responsible for building and maintaining a part of the system that depends heavily on specialist knowledge, to the extent that most team members must be specialists in that area of knowledge to understand and make changes to the subsystem.

—Matthew Skelton & Manuel Pais - Team Topologies, page 91

Conclusion

Development team specialization is often misunderstood or overlooked. It can have disastrous effects on an organization’s ability to deliver working software consistently. It often increases lead times and is a barrier to continuous delivery.

I recommend:

- Populating teams with a mix of specialists and generalists

- Hiring specialists with a focus on learning and collaboration

- Hiring specialists who are on a path to becoming E-shaped contributors

- Encouraging collaborative development practices on teams (team-based design, mob and pair programming)

- Creating an environment where learning happens on the job during the workday (learning hours, code katas, etc.)

- Organizing teams for few to no handoffs (individual teams can deliver features end-to-end)

- Creating complicated subsystem teams where necessary for complex domain knowledge, but use them sparingly

-

Examples of Complicated Subsystem Teams from the book _Team Topologies: Organizing Business and Technology Teams for Fast Flow. ↩