The Bolden Rule and Software Development Teams

19 Aug 2021 . coaching . Comments #coaching #anti-patterns #consulting

There are a handful of books that have had a significant impact on me. One book, in particular, inspired me to become a software consultant, Gerald Weinberg’s The Secrets of Consulting. If you don’t know who Weinberg is I suggest reading his Wikipedia entry as a first step. He was a well-known software consultant and author, having written over 40 books in his lifetime. His books are timeless and I find myself returning to them from time to time and getting more out of them each time I read them. As I read through The Secrets of Consulting again, I realized that we can apply his Bolden Rule to help software organizations and their leaders improve.

The Bolden Rule: If you can’t fix it, feature it.

—Gerald Weinberg - The Secrets of Consulting

If you work in software development, marketing, or happen to work adjacent to those industries you’ve likely encountered the the Bolden Rule, though not necessarily by name. The Bolden Rule states simply, “If you can’t fix it, feature it!” Weinberg provides several examples of the Bolden Rule he has collected. Before we get to how it can be applied to help software organizations improve, I’d like to share my favorite Bolden Rule example.

Intellivision’s Bolden Rule Moment

Evan-Amos, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Evan-Amos, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

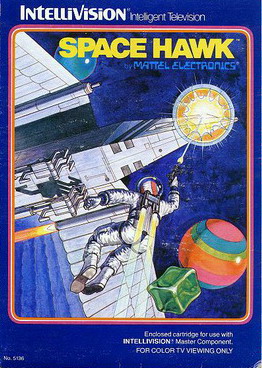

I was a young child in the early 1980s with three older siblings. That meant that I got to experience what is referred to as the second generation of home video game consoles. Our family had an Intellivision console, Mattel Electronics’ response to the Atari 2600. Development for the Intellivision started in 1977, the same year the Atari 2600 was released. We amassed a lot of games for the console over the years, and I played it long after my friends had moved on to the next generation, specifically the Nintendo Entertainment System.

One of my favorites was a game called Space Hawk, and it just so happens to be the Intellivision’s Bolden Rule moment. Space Hawk was Mattel’s attempt at their version of the popular game, Asteroids. In Space Hawk, you are floating through space with a rocket-powered space suit shooting at various hazards (the titular Space Hawks, bubbles, comets, etc.) before they come in contact with you. If you are in danger you can press the hyperspace button. Hyperspace relocates your character to a different part of space, but not without a cost. Each time hyperspace is used the player’s score is decreased.

During the testing of the game, a bug was discovered in the code that was triggering hyperspace. When simultaneously pressing the directional disc in a certain direction and pressing the side action buttons (which fire the player’s weapon) a hyperspace button press would be triggered. This directional disc and side-action button combination is critical to the gameplay, so it was a very common bug. However, the team couldn’t solve the problem and deadlines were fast approaching.

Faced with a situation where they couldn’t fix the bug and had run out of time, the Space Hawk team decided to modify the instruction booklet to feature it. The Space Hawk Instructions (see page 3) describes that the player may encounter black holes in space from time to time. When they encounter black holes, hyperspace will be triggered automatically saving the player from certain death, but still causing them the reduction in their score. And just like that, the bug became a feature of the game that added some variability to the gameplay.

The Bolden Rule Applied to Software Organizations

On the surface, it may seem like a terrible idea to apply the Bolden Rule to software development, right? Teams who produce bugs that they struggle to fix certainly shouldn’t be looking to turn these bugs into features. But what if instead of applying it to bugs in the code, we apply it to the way software development teams work? What if those of us in positions of influence can apply the Bolden Rule to help change the thinking of organizations? I contend that anyone, software engineers, managers, consultants, anyone with some influence can apply this rule.

Let’s look at a very common, but misguided example. Nearly every software organization wants its teams to create code faster. Typically software organizations try the same things over and over again to no avail. They add more developers because surely more hands-on keyboards will create more code in less time. They add more process and more management because that should help make the team more “efficient”, and ensure everyone is constantly busy (i.e., there is no slacking on the job). When these practices slow the development workflow rather than speed it up what is the typical reaction? Often it is to add more people, add more process, and add more micromanagement. Soon enough the organization finds itself in a vicious cycle.

What if we look at the team’s speed of development not as the bug that needs fixing, but the feature? What could we do differently? Maybe instead of adding more developers, more processes, and more management, we would:

- Begin to focus on customer outcomes instead of the output of code

- Focus on practices that reduce cycle time and deliver work more safely rather than making sure everyone is busy. Practices like decreasing work-in-progress (WIP) and collaborative development techniques (e.g., pair and mob programming)

- Identify the smallest increments of value that can be delivered

- Focus on practices that help to prevent rework

- Find ways to automate repetitive tasks

- Improve the speed, accuracy, and frequency of feedback loops (automated tests for example)

- Work in smaller batches

So much of what makes software teams great works against a century of Taylorism and people’s instincts. If the Bolden Rule can be used to help challenge an organization to stop trying the same old techniques, it is a worthy tool to wield.