Avoiding Automated Testing Pitfalls

How to Create Sustainable Test Suites

20 Oct 2019 . software craft . Comments #agile development #unit testing #anti-patterns

There is a pervasive problem in the software industry stemming from a misunderstanding of automated testing. Companies are investing increasing amounts of money and time into automated testing strategies and test suites, but are not seeing an increase in quality or value delivery to customers. Thankfully automated testing is now being seen as a necessary complement to manual, exploratory testing. However, many organizations don’t understand the costs and benefits of the various types of automated tests available to them.

Two big misconceptions set the stage for a risky and expensive approach to automating tests. First, is the idea that automated testing is the process of automating the steps of manual QA; automating the script the manual tester would follow. Second, is that these automated tests should be written by the QA organization, outsourced, or written by a team of “test engineers” who are not the team writing the software being tested. These misconceptions are travel companions. I rarely see one without the other, and it spells trouble for the software organizations trying to build their automated test suites.

Who is Responsible for Quality?

Often I see this mindset take hold in organizations that are struggling with establishing cross-functional development teams. They cling to the outdated idea that “testing is QA’s responsibility” and developers should be focusing on writing production code. This disconnect makes it very difficult for organizations to improve their automated test strategy. In companies like these, I often remind them that cross-functional teams own their quality, not a department.

The Risks of End-to-End Focused Testing

As compared to lower-level tests, end-to-end tests are slow and brittle. They require a significant amount of time and often many people to keep the tests working and to investigate whether failing tests are false failures or real failures. Worse still, test suites occupied by a majority of these tests create a false sense of security for the organizations that rely on them. False failures are like broken windows and people begin to doubt failing test suites, “Is this a real failure or an expected failure from a code change?” Because these tests can never cover all of the branching and business logic of the system, the suite lulls the organization into a false sense of security.

Lacking error-localization

End-to-end and UI-driven tests cover so much scope that they lack error localization. A failing test can cost the organization a significant amount of time to determine whether the failure was indeed a real failure. When legitimate failures are caught, additional time is spent finding the code that caused the error and determining where it should be fixed.

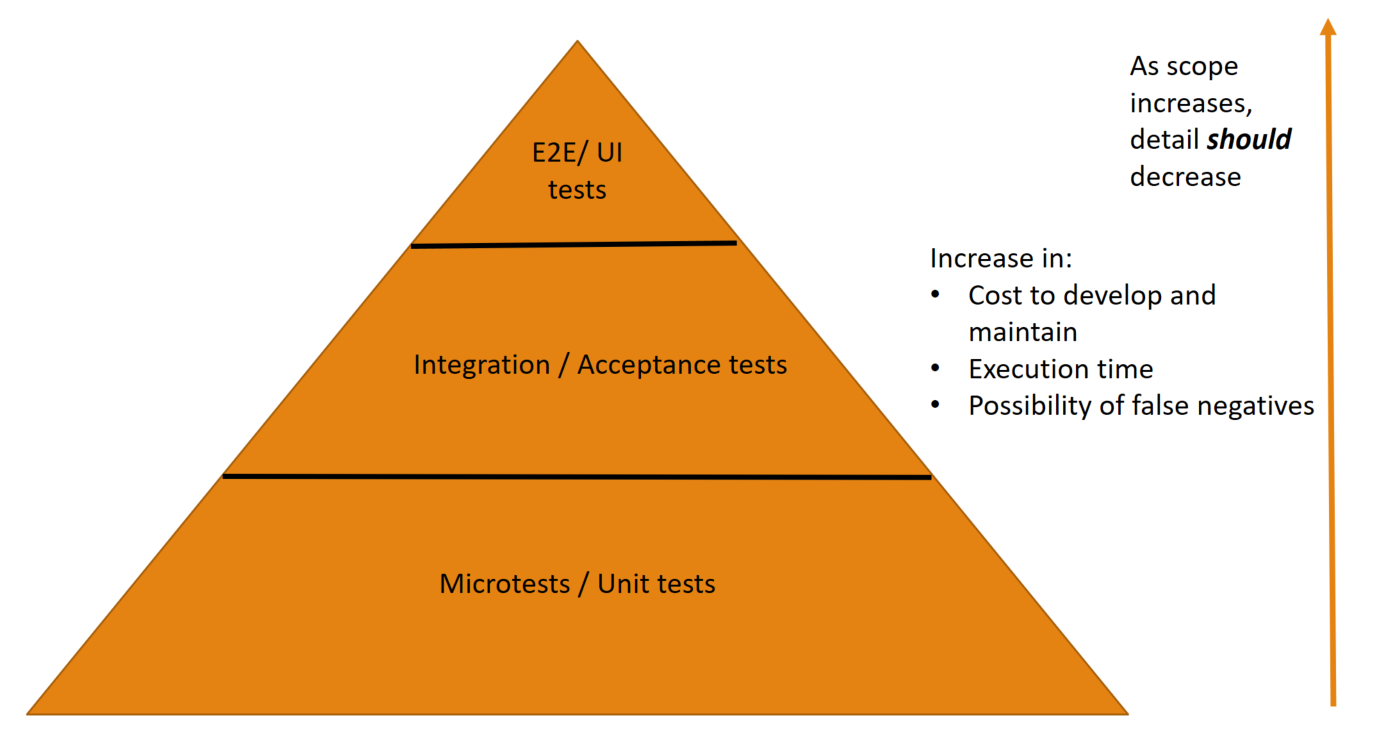

The Test Pyramid

In these organizations, I recommend sharing Mike Cohn’s Test Pyramid. While it’s not perfect (no model is), it is an effective way to show organizations how to structure their test suites to get the most benefit from them. The pyramid makes it clear that organizations are spending most of their time and money on the wrong category of tests when they invest heavily in complex automation testing frameworks and end-to-end tests.

The test pyramid describes an approach to creating sustainable test suites. The bottom of the pyramid consists of unit tests or, more recently known as, microtests. The majority of the test suite should consist of these tests. There should be a lot of them, they should be VERY small, verify a VERY small area of code (i.e., a few lines of production code) and they should be VERY fast (i.e., they should run in a few milliseconds). These tests should be able to run in isolation on developer computers.

The tests that occupy the middle tier are the integration and acceptance tests. These tests cover more system scope and are more “connected” (e.g., they connect to a database, the filesystem, etc.) than microtests, so there should be much fewer of these in the test suite.

Finally, the top is UI-driven or end-to-end tests. There should be very few of these, as they take longer to execute and have an increased likelihood of identifying false failures.

The Inverse Relationship of Scope and Detail

The most important thing to understand in this pyramid is the inverse relationship between scope and detail. At the bottom of the pyramid, microtests should be testing all of the detail of the system so their scope should be very small. They should verify only a few lines of code in the system. As you move up the pyramid, the scope of the test should increase. When scope increases the detail should decrease.

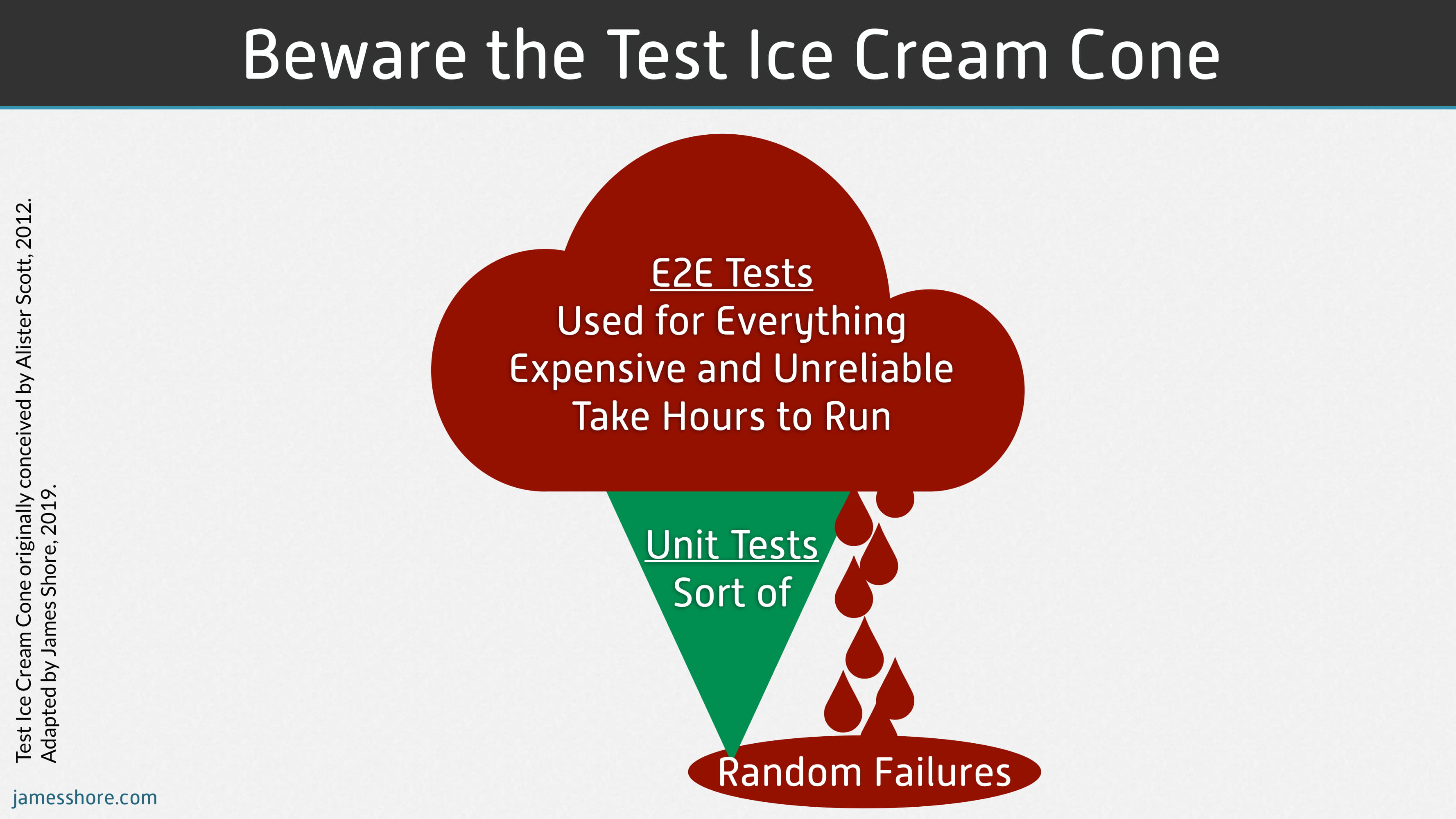

The Big Failure

The biggest failure of end-to-end focused test suites is that they try to test both high detail and large scope. This is the recipe for brittle and unreliable tests.

Organizations adopt UI-testing tools like Selenium and attempt to wrap them in complex, homegrown testing frameworks. They use these frameworks to create comprehensive suites of end-to-end tests to replace manual QA testing, without understanding the drawbacks of this approach. I’ve seen custom frameworks that use Cucumber (which is a fine tool for BDD) to drive UI-testing-tools to eventually exercise end-to-end tests. So much of the organization’s time and money is spent creating and maintaining this complex framework and the brittle tests the framework supports.

The Test Ice Cream Cone

The result of this approach is the Test Ice Cream Cone, where a majority of the test suite is occupied by end-to-end and UI-driven tests. When I encounter this, my goal is to help the organization shift their focus towards aligning their test suite to the test pyramid.

Push Tests Down

Some organizations will resist minimizing these end-to-end tests because they managed to find an issue before it got to production. They see these tests as beneficial since they have decreased the time it takes for manual testing. It’s understandable to see why they wouldn’t want to abandon these tests, however, the fact remains that they are slower and less reliable than tests lower in the test pyramid. My advice has always been to push tests down. If a bug was caught in an end-to-end test or integration test, write a microtest that exposes the bug and then fix it. I was very pleased to see similar advice in The DevOps Handbook.

Not only are errors detected during integration testing difficult and time-consuming for developers to reproduce, even validating that it has been fixed is difficult (i.e., a developer creates a fix but then needs to wait four hours to learn whether the integration tests now pass). Therefore, whenever we find an error with an acceptance or integration test, we should create a unit test that could find the error faster, earlier, and cheaper.

—Gene Kim, Jez Humble, Patrick DeBois & John Willis - The DevOps Handbook - Chapter 10

There is an argument that microtests and unit tests can’t catch every bug. While I think this is true, it’s often because of a gap in the microtests or a quality issue with the tests. It’s frequently not because of an inherent failure of that category of test. When this argument is employed, teams miss an opportunity to improve their microtests.

Lacking Microtests

The most common reason organizations adopt this approach is because they are lacking a high-quality and trusted unit test / microtest suite. Often teams abandon unit testing because they struggle with trying to wrap unit tests around untestable code. Other teams may fight through the challenges and wrap unit tests around untestable code and end up with a suite of tests that are a drag instead of an accelerator.

You can’t write good tests for bad code.

—Unknown

The Importance of Team-Owned Tests

Organizations that outsource testing to another team or department to try to “free up development teams” to focus on features miss the point. The best tests are the ones that can probe within the boundaries of the system. When testing is outsourced to another group or QA department (who aren’t experts in the code that is being tested) they can only test from the perimeter. The book Accelerate, which describes the science and research behind high-performing and successful software teams, concluded that automated tests that were outsourced to the QA department or another team showed no correlation to organizational performance.

Developers primarily create and maintain acceptance tests, and they can easily reproduce and fix them on their development workstations. It’s interesting to note that having automated tests primarily created and maintained either by QA or an outsourced party is not correlated with IT performance. The theory behind this is that when developers are involved in creating and maintaining acceptance tests, there are two important effects. First, the code becomes more testable when developers write tests. This is one of the main reasons why test-driven development (TDD) is an important practice—it forces developers to create more testable designs. Second, when developers are responsible for the automated tests, they care more about them and will invest more effort into maintaining and fixing them.

—Nicole Forsgren, Jez Humble, Gene Kim - Accelerate: The Science of Lean Software and DevOps: Building and Scaling High Performing Technology Organizations - Chapter 4

Turning the Ship Around

For software organizations to improve their test suite situation they should start by mapping their tests to the test pyramid. They should place their largest investments in the lowest level tests, which means a focus on microtesting. All new code should come with microtests, which will require teams to learn and improve their Test-Driven Development and microtesting skills.

As they build out the base of the pyramid, they can begin to phase out complicated end-to-end testing frameworks and outsourced test suites. Teams should own their test suites and decide how many if any, end-to-end and UI tests they will need. While I believe some level of end-to-end tests is important they aren’t always necessary.

Conclusion

One key attribute of successful, high-performing software teams is the reliance on fast feedback loops. Test suites are one of the main feedback loops available to teams. Focusing on fast, reliable, repeatable tests is an accelerator for software organizations. Automated test suites are essential, but be aware of the pitfalls in creating them.

Further Reading

- Test Pyramid - Martin Fowler

- The Practical Test Pyramid - Ham Vocke

- Test Pyramid: The Key to Good Automated Test Strategy - Tim Cochran