The Delivery Trap

03 Sep 2018 . leadership . Comments #anti-patterns

In Erik Dietrich’s book, Developer Hegemony - The Future of Labor he describes what he calls “the Delivery Trap.” To briefly summarize a chapter’s worth of content, software developers are caught in a delivery trap, being judged by their organization solely based on their output. For those who want to advance in their organization, like those who occupy the C-Suite, they need to escape this delivery trap and be judged instead by narratives that they can manage.

There’s another form of this delivery trap that grips feature factory software organizations. If you are unfamiliar with feature factories, the term was coined by John Cutler in his article 12 Signs You Are Working in a Feature Factory. This delivery trap is the result of an organization that is laser-focused on team output and pushing new features through the system as quickly as possible; essentially robbing teams of autonomy, mastery, and purpose. These organizations deliver prescriptive, overly specified solutions to teams for them to implement, treating them like order takers, or “digital ditch diggers” as described by this article about the Trap of Sales Driven Development. These organizations tend to separate the decision makers from the workers, creating a buffer between teams and their customers. All information must flow through another organization of decision makers who don’t get their hands dirty building the actual software.

Maintain the Status Quo

Once someone is on a development team in these organizations the best they can do is maintain the status quo. They are stuck in an endless cycle of getting their work done by the end of the sprint and chasing their estimates (made with very little information) and velocity commitments.1

The Harm of Velocity and Point Estimates

Too often velocity is treated not as a short-term planning tool for the team, but rather a productivity measure examined by management. The goal quickly becomes an ever increasing velocity. Any decrease is a cause for alarm to be discussed by leadership. Teams treat sprints like clown cars, jamming as many story points into them as possible. I’ve seen teams debate for more than a half hour about how many additional points above their average velocity they should “commit to.”2 An increasing velocity must prove that they are working hard and generating output.

Sprints aren't clown cars. They're like taxis-only fit so much. Out with six friends: two taxis. ^ @AgileEvolution_ pic.twitter.com/sBCAeHIFoy

— AgileFortune (@AgileFortune) July 11, 2016

Additionally, it is common to see long term projections based on velocity and estimates, which in turn creates an unending pressure to keep velocity high and a focus solely on new feature work. If developers are judged by velocity, output, and estimates, they will avoid any activities that could put these at risk. It just so happens that they avoid the very same activities that are common to high-performing teams:

- Continuous Improvement

- Continuous Learning

- Experimentation

- Short Feedback Cycles

These teams are now hamstrung, with no hope of improving the organization, their work, or the quality of their codebase in any substantive way. They are no longer knowledge workers, only a set of hands banging on a keyboard. I often refer to these folks as company typists.

Improving daily work is even more important than doing daily work

— Gene Kim - The DevOps Handbook

Who Improves the Work?

These organizations have fallen into the delivery trap. One simple way to identify if a company is caught in a delivery trap is if the people who are trying to make any substantial change have to escape the cross-functional delivery teams to do so.

Delivery Trap Narratives

Here are some examples of the kinds of things you’ll hear in an organization stuck in the delivery trap:

We need improvements to our build pipeline and build speed, we’ll give that work to Nancy. This would distract a team from their “real work.”

We need to identify tools to test our new API. We’ll give it to someone who isn’t responsible for building the APIs - someone outside of a delivery team. They’ll figure it out and show the teams how to test their APIs.

The architecture and overall design of the system hasn’t improved in years, we must have lazy software developers. What we need is a separate architecture organization. Then our architects can operate outside of these cross-functional delivery teams to make the improvements and push them down to the teams. The teams have already had plenty of time to improve it themselves.

Forgetting the Lessons of Lean

One of the many things we’ve learned from Lean Manufacturing, and later Lean Software Development, is that the best way to improve the work is for the improvements to come from those doing the work. They are the experts and closest to the work. Sayings like “Move authority to the information” have become mantras to remind people of the importance of this practice.

All of these misguided efforts to shift the real improvements outside of teams masks the problem and continues the cycle of the delivery trap. Developers are told they should improve the system, but are incentivized to do just the opposite and keep churning out output. Developers are stuck in a vicious cycle until they’ve had enough and leave to find employment elsewhere. I’ve seen too many great software developers leave companies, feeling undervalued by the organization since they were treated as typists and order takers; their only value being an extra set of hands to meet organizational deadlines.

Breaking Free

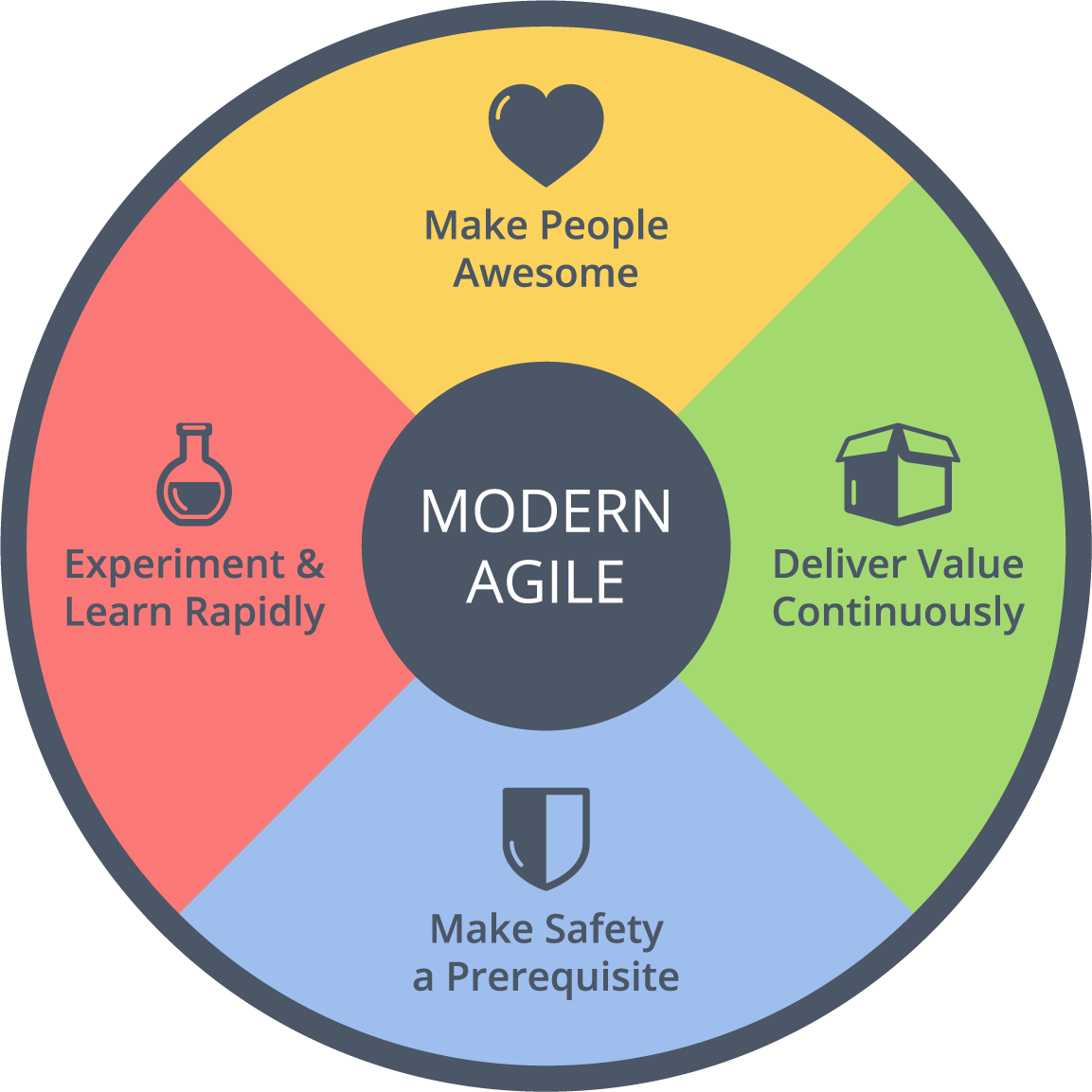

To break this cycle leadership must commit to making a large cultural change and adopt the practices that will help them escape the delivery trap. These can be found in Lean Manufacturing, Lean Software Development, Extreme Programming (XP), DevOps, and Modern Agile.

If an organization makes a serious commitment to the four principles of Modern Agile, the Three Ways of DevOps, or the practices found in Lean Software Development and XP, a seismic shift will occur. Autonomous teams will begin to emerge who make the decisions about their work, interact directly with their customers, and consistently improve their work - since they are the ones who are most qualified to do so.

The Three Ways of DevOps

- The First Way: Systems Thinking

- The Second Way: Amplify Feedback Loops

- The Third Way: Culture of Continual Learning and Experimentation

Instead, if companies continue to focus on output, they will never break free of the delivery trap that is an all too common attribute of poor Scrum implementations3.

-

I mention sprints and velocity because I’ve seen this delivery trap specifically in organizations practicing Scrum or SAFe. ↩

-

You won’t find the phrase “commitment” mentioned in the latest version of the Scrum Guide. ↩

-

These poor scrum implementations are described in Ron Jeffries’ series on Dark Scrum and Martin Fowler’s post on Flaccid Scrum ↩