SOS - To Save Sinking Test Suites

30 Jan 2018 . development practices . Comments #unit-testing #tdd #code-quality

I’ve often heard developers declare that unit testing doesn’t work only to discover a test suite full of complex, brittle, and unmaintainable tests. Fortunately, with a focus on readability and simplicity, bad test suites can be rehabbed, becoming accelerators for development teams.

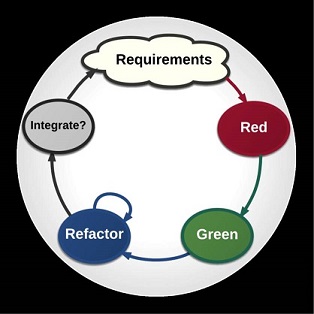

Test-Driven Development

Every time I discuss high-quality unit tests I also encourage practicing Test-Driven Development (TDD). It prevents a significant number of issues that arise when developers try to cover bad code in tests. I am a firm believer that you cannot write good tests for bad code. Unfortunately, testing after the code is written, often leads to software design issues and problematic tests. Test After Development (TAD)1 yields tests with much less value that bypass all of the benefits of Test Driven Development, some of which I’ve written about here.

The Code Quality Litmus Test

When practicing TDD tests are the first consumer of a new object. This ensures that objects are designed for their consumers first and foremost. This becomes a much more daunting challenge when designing code without using TDD. Unit tests act as a litmus test for the quality of the code. Tests with a lot of setup, control flow logic / conditional statements, and many collaborators are signs that there are design issues with the tested code.

SOS

When I coach developers on writing high-quality unit tests I use the mnemonic SOS. Tests should be small, obvious, and simple. The attributes of high quality tests and the heuristics to create them can be grouped into these three categories. Teams that support low quality code and complex test suites are in a constant state of distress and often still taking on water. Using a maritime distress signal as a mnemonic seems appropriate to help teams remedy these problems.

Small

Test Size

I recommend that unit tests should be small. In fact, I prefer using the term “microtests” (a term created by GeePaw Hill) since it better describes the qualities of valuable unit tests. Often people will ask “how small”, looking for a specific number. I believe microtests should be around 15 lines or less and should take about 60ms to run. Much more than that is an indicator of a design problem. There’s no exact number, but we should always strive to keep them small and fast.

Does the object require a lot of complicated setup? The callers of that code are going to also need to understand all of that complicated setup. I can assure you that they shouldn’t need to know that. Some developers avoid this by putting complex test setup in the xUnit Test Setup method. This unfortunately obscures the test and ignores other heuristics.

Are there a lot of dependencies that need to be setup? That’s a sign that the object is doing too many things,and becoming a God Object. It’s an indication that there is an abstraction (or several) missing that should collect a few of those dependencies into a single object.

Test Scope

Another small characteristic of microtests is the scope of the test. Tests with a very small scope provide error localization. When a test fails it is important to be able to find the source of the failure immediately. When the appropriate use of test doubles is avoided, a majority of the test suite becomes integration tests, creating problems for error localization.

Larger test scopes lead to overlapping tests. Test overlap is often the source of unnecessary tests, which increases the suite run time. Additionally, large test scopes introduce multiple test failures for a single change.

Obvious

Tests should be obvious. Any developer should be able to look at a test and understand it (and the code it’s testing) within a minute or two. Tests are valuable executable documentation, but to realize this value, care must be taken to keep their intent obvious.

Keep Tests Self-Contained

An important heuristic is that tests should be self-contained and independent of one another. xUnit’s test setup should be reserved for very specific usages. I recommend using test setup only to create the object under test, initialize its dependencies, and inject them manually into the test subject’s constructor. This assumes that the test subject is shared between test cases in the same fixture.

If there is some duplication of test setup, but it is important to the outcome of the test, I prefer extracting it into a well-named private method rather than putting it in a setup method. This makes its usage obvious in each the test case. Sometimes the specific setup is so important to the outcome of the test that explicitly calling the setup code in the test case can be the best option. DRYing tests should be used to enhance understanding. If instead it produces the opposite effect, it should be avoided.

Arrange-Act-Assert

Arrange-Act-Assert is a common pattern for unit tests. In order to make tests obvious, they should conform to it, or the Given-When-Then pattern common to Behavior Driven Development. This pattern can be amplified by ensuring that a separate block of code exists for each step. Any refactoring that would remove one of these code blocks should be avoided. I often violate this rule if the test is so simple (consisting of a line or two) that creating the three blocks doesn’t enhance understanding.

Obvious Code Coverage

One of the reasons to adhere to Arrange-Act-Assert is to make code coverage obvious, which is another characteristic of a high quality test. When Arrange-Act-Assert is followed the middle block, often consisting of a single line, is the method under test. It is obvious that the test coverage is the method being called in the Act block.

Common Naming Conventions

Every test fixture and test case in a suite should conform to a common naming convention. By simply reading the test method the reader should understand what is being tested, the expected outcome, and the scenario it is being tested in. There is a lot of advice available on naming tests. More important than the specific format, is that the format is adhered to throughout the test suite.

Common Test Constructs

I ensure that common test constructs all use the same terminology. Every test case has a subject, the object that is being tested. It is always called “subject” in the tests I write. Tests make assertions against a result. The response returned by calling the method under test I always name “result.”

Amplify and Obscure

Extracting test setup into well-named, intention revealing private methods, keeps tests simple and obvious. When setup can be shared across fixtures, those private methods can then be extracted into classes and Object Mothers. I recommend keeping setup in the test cases themselves if it is important to the outcome of the test, thus amplifying its importance for the reader.

Setup that is less important to the test can then be extracted into other objects so that it can be obscured. This signals to the reader that they don’t have to spend time reading those details to understand the test.

Glance Test

By following these steps to make tests obvious, they pass what I call “the glance test.” I can glance at a test and in a minute understand what is being tested, why it’s being tested, its collaborators, and how it should react under the documented test conditions. Since code is read many more times than it is written, unit tests (same as the code they test) must pass this glance test.

Simple

Simple tests also tend to be small and obvious tests. These categories are related to each other, so optimizing for one often optimizes for the others.

Use Test Framework Extras with Care

xUnit test frameworks come with a lot of extras. In some cases, they can help make tests more expressive and reduce duplication. However, it is just as likely that they are a workaround for a design issue and add complexity to the test. Often these extras negatively effect the ability to scan the test quickly and fail the Glance Test. For microtests, I avoid setup at the test fixture level (remember tests should be independent) and xUnit extras like MSTest’s ability to test private methods or many of NUnit’s custom test attributes.

Contain No Branches or Control Flow Logic

Tests should not contain any branching or control flow logic. Their existence is a code smell. Refactoring the code under test can obviate the need for branching in test cases.

Logic in tests confuses the story of what’s being tested. Test-scoped logic is hard to read and errors are easy to miss.

— Justin Searls, RubyConf 2015

Tests are Untested Code

One of the most important points Justin Searls makes in his RubyConf 2015 talk, How to Stop Hating Your Test Suite is that tests are untested code. Introducing conditional logic and flow control structures means that there are now alternate paths through a test. This creates an opportunity for bugs to be introduced. We test all conditional logic in production code. Writing tests with conditional logic requires tests for tests to ensure they are correct.

In fact the most convincing reason to keep tests simple is that they are untested. Bugs in tests provide a channel for bugs in production code to go unnoticed.

Putting it all Together

Take a look at the following example of a microtest that puts all of this advice together.

Further Reading

For more detailed advice I’ve written a series of posts about how to create high-quality, valuable tests:

- Should Private Methods Be Tested?

- Unit Test Refactoring and Avoiding Complexity

- Follow Consistent Test Patterns

- Extracting Methods in Unit Tests

I also recommend these three talks on creating and maintaining valuable unit test suites

- Justin Searls - How to Stop Hating Your Test Suite

- Gerard Meszaros - Find the Right Abstraction Level for your Tests

- Sandi Metz - The Magic Tricks of Testing

-

Test After Development or TAD is discussed in this article about TDD by Jeff Langr ↩