Misconceptions of Pair Programming

30 Nov 2017 . development practices . Comments #pair programming #extreme programming

Pair programming has increased in awareness over the last 20 years since its inclusion in eXtreme Programming (XP). Despite this increase in awareness, it remains misunderstood and under utilized by agile software teams. In this post, I am going to describe some misconceptions of pair programming. Then, in a follow-up post, I will discuss its benefits and how to encourage the practice in organizations that have doubts about its merits.

I recommend pair programming as an essential practice for modern development teams. By dispelling some of the myths and misconceptions and focusing on its benefits, it will hopefully encourage more organizations to master this practice.

These misconceptions have their genesis in old Information Technology (IT) project practices that treat software development like industrial revolution era factory work. Companies are often slow to change. As a result, these beliefs can be found entrenched in organizational processes preventing companies from achieving excellence. Creating great software is a process of discovery, and like most knowledge work, it is a creative endeavor. We need to start shedding these old beliefs to achieve better outcomes for our customers and create the next generation of brilliant technologists.

The Feature Factory Mindset

The most common argument against pair programming is the belief that it is two people doing the work of one person and therefore it must reduce the productivity of the team by 50%. Believing that software development is a mechanical process and not the creative endeavor that it is leads people to believe that developers working together slows them down. If organizations continue to measure the value of software development in output, they will most likely avoid a practice like pair programming (despite the fact that studies have shown that it does not result in decreased output). When optimizing for 100% utilization of “development resources” and measuring a team by their velocity, organizations are unlikely to try pair programming.

The Costs and Benefits of Pair Programming

Agile Manifesto co-author Alistair Cockburn and Laurie Williams (from the University of Utah) published a study, the Costs and Benefits of Pair Programming in 2000. In the study they describe that there is not a 50% decrease in team productivity, as one would assume if “two people were doing the work of one.” What they did find was that there was an increase of 15% in development program hours for teams who pair. However, there was a reduction in bugs escaping to production, an increase in the quality of the code, and other benefits (that will be mentioned in a future post) that more than made up for the 15% increase in initial development hours.

If we shift the measure of team success from output to value delivered to the customer, there is a compelling case for pair programming. It often results in delivering value faster, given the higher quality code it yields and its support in limiting work in progress at the team level.

Selective Pair Programming

The other misconception that I often hear typically comes from developers. It is the idea of “Selective Pair Programming”, sometimes referred to as “Pragmatic Pair Programming.” The thought is that pair programming, as described by XP, is too prescriptive. Instead teams will “only pair when it’s appropriate.” The problem with this approach is that it assumes that developers can become experts at pairing without practicing it.

These teams reserve pair programming for very specific circumstances, like onboarding a new developer or helping a teammate out when that person gets stuck. They avoid it in the typical day-to-day work, favoring working alone over working collaboratively.

I’ve heard teams who selectively pair program make remarks like “we would never pair on all of our work…only when it makes sense, where it is appropriate” insinuating that pairing more often then what they feel is correct is somehow unprofessional. Unfortunately, pairing when someone gets stuck is not how I define pair programming (and I think the XP founders would agree with me). I expect a high amount of collaboration on software teams, and pairing on the day-to-day work is a great way to achieve that.

Sometimes pair programming doesn't "take" -- most frequently when it's framed as one programmer helping out another who's struggling.

— Tim Ottinger (@tottinge) October 5, 2017

Software Development is a Social Activity

One of the problems with teams who only selectively pair is that software development is a social activity. Great software gets created by teams who are great collaborators. Teams who pair program are highly skilled collaborators. Teams who rarely pair, or don’t pair at all, tend to struggle with collaboration.

Watching a skilled XP team work is an amazing thing to behold, and it shows how different they are from traditional development teams. Their team area is a hive of activity. For example, you may find three developers at a white board diagramming a solution, a developer sitting with two QA members discussing corner cases for a feature being developed, and two other developers pairing on a task. The room is in constant motion and there is a consistent level of noise (the sound of collaboration). The energy is palpable. It is obvious that something creative and special is happening on these teams.

To contrast this, observe a team that “selectively pairs” and you will find a very different scenario. What I see most often is the backs of developer heads buried in computer monitors with headphones on. The room is completely silent as very little collaboration happens. It seems much more like a library than a place where software is being created.

Pairing Takes Practice

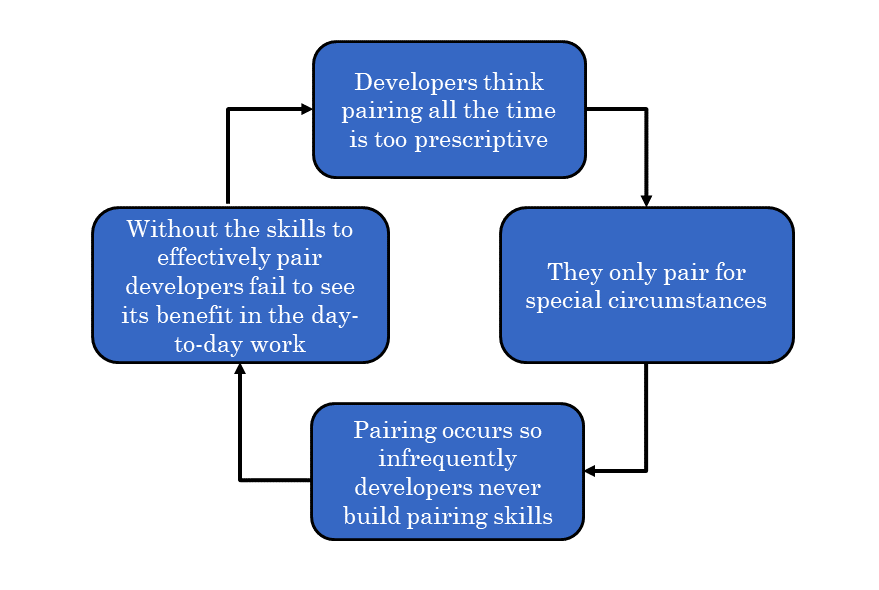

Pair programming is a deceptively challenging technique and it, like other practices, requires consistent practice and repetition to improve. Teams who only pair in very specific circumstances never gain the skills required for effective pairing. This results in them utilizing it less often. The less they do it the less useful it is for them. This creates a vicious circle that results in teams never realizing the benefits of pair programming.

The Selective Pair Programming Catch-22

I refer to this as the Selective Pair Programming Catch-22

Time for Pairing

On the surface I would agree with the idea that teams shouldn’t be required to pair on 100% of their work. However, my view of how much teams should pair, and the view of developers who have not mastered pair programming, is often quite different. I would recommend pairing (or other collaborative techniques) used for a majority of the work. For a team that is just learning these practices, I would expect them pairing nearly all of the time until they master the practice.

The teams I’ve observed who claim to selectively pair program tend to pair significantly less than this. Pairing on the day-to-day work is a rare occurrence. It is certainly not the level of collaboration I would expect from a modern, agile software team. These teams end up missing the many benefits that come from pair programming and team collaboration.

Conclusion

When making a case for pair programming I find it useful to both understand the misconceptions associated with it, and also to be able to articulate the laundry list of benefits to the software team and the larger development organization. Those benefits will be discussed in my next post.