The Vicious Circle of Rewriting Software

27 Nov 2015 . software craft . Comments #code quality #coaching

When adding a feature, if the only recourse a team feels it has is to rewrite a significant amount of code, this is indicative of code quality issues in the organization. This should be a red flag, and it should be something that is addressed in team retrospectives until it is remedied. This rewrite cycle is something that is so commonplace in some organizations that it is not questioned. “This is version 3 of feature x, version 5 of feature y.” Each one of those versions has been a delete and rewrite cycle. Unfortunately, this prevents the developers involved from ever mastering the skills necessary for creating and maintaining high-quality code.

It surprises me how many organizations believe that a code rewrite is an appropriate and even necessary course of action when adding features. This is a failure of the development organization to build the code in a way that supports extension. These rewrites are not good for the organization. They require a large development and testing effort and are fantastic opportunities for reappearing bugs. Those bugs that have been fixed over time but reintroduced through poor programming practices. The time and effort spent on rewrites could be used in much more productive ways by the organization.

Rewrite Scope

One of the gray areas on this topic is how much rewritten code is an appropriate part of code maintenance and how much is not. Rewriting individual methods and even individual small classes, when the code is covered by unit tests, can be the appropriate decision when adding features. This “rewrite in the small” can be part of a larger refactoring effort. In fact, Martin Fowler’s book Refactoring, contains the Substitute Algorithm Refactoring that describes rewriting a method covered by unit tests. However, even in many of these cases there are refactoring steps that can get you from where you currently are to your destination design safely, without unintentionally modifying the behavior.

In well designed software, where methods and classes are very small, rewriting a method or class amounts to rewriting a very small amount of system functionality. In a recent .NET Rocks podcast featuring Justin Searls, he talks about Mature TDD. Specifically he describes how TDD allows him to break down problems into such small components that adding features usually results in rewriting some very small classes as part of his refactoring to add new features. This helps keep the code in a maintainable state such that a larger rewrite is never necessary.

However, by contrast, in poorly designed systems deleting a public method or a class could result in a significant amount of functionality being deleted and rewritten. Often this is done without an existing unit test suite. In my experience developers will call this delete and rewrite activity “refactoring.” However, it bears absolutely no resemblance to actual refactoring and utilizes none of the techniques to ensure that behavior is maintained while deleting and rewriting.

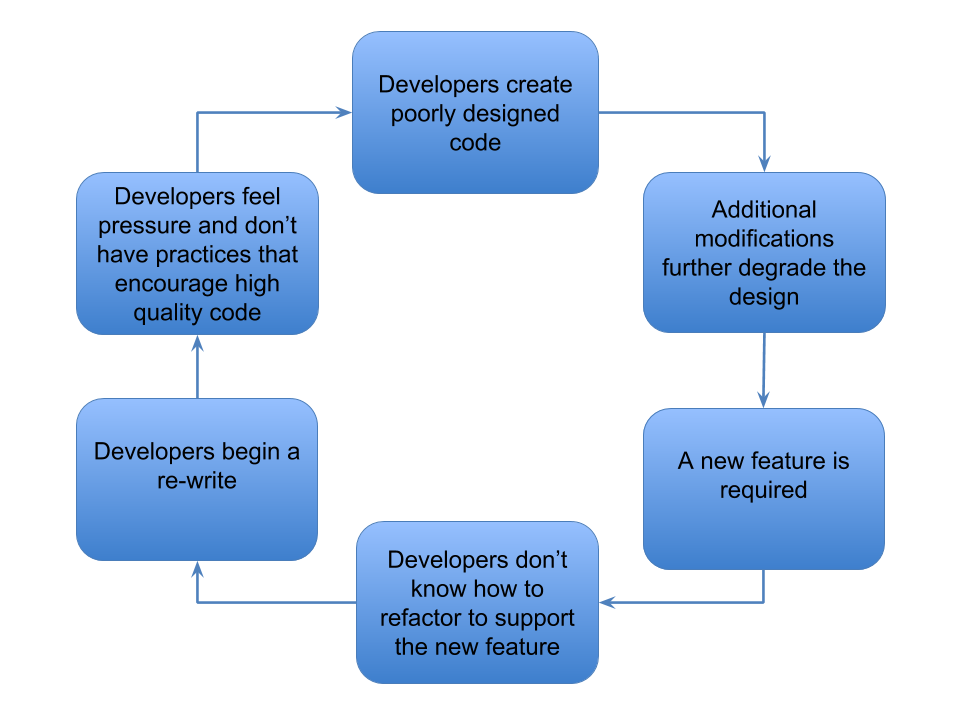

The Circle of Unmaintainable Code

The source of these rewrites is usually two-fold.

Poorly Designed Code

The team does not write well-designed code. The code is tightly coupled, not testable and difficult to change. This is usually the result of a skill gap on the team that is not being addressed. This is common for organizations who believe code quality is subjective, or that the only measure of quality is that the QA team did not find any bugs. Often times these teams feel pressured by the larger organization to churn out features by strict deadlines. These teams also tend to not adopt practices that encourage high-quality code.

A common practice that leads to these code problems is that developers determine a design up front. They feel pressure to complete the feature quickly. While implementing the feature they don’t take the time to re-examine the design when it becomes obvious that it is not working. They push through their original design which results in very poor quality code that is now a tax on the entire organization. I see this practice often, and try to encourage practices like TDD to prevent these code messes from being created.

Lack of Refactoring

The team does not continuously refactor code. This results in every subsequent code change further degrading the quality of the code. The problem is compounded because the code started out in a state that makes it very difficult to maintain.

Without breaking the circle, developers will continue rewriting and recreating unmaintainable code until eventually the entire system is deemed in need of a rewrite. A significant amount of time and effort is put into these feature rewrites which never result in increasing the overall quality of the code. These rewrites only ensure that another rewrite is coming some time in the future.

The Grand Redesign in the Sky

If you haven’t read Robert Martin’s Clean Code, I highly recommend it for many reasons. Not the least of which is a section from the first chapter on this topic. The section The Grand Redesign in the Sky, in its short few paragraphs, accurately describes how these redesigns end up suffering from the same problems as the systems they are replacing. They end up as unmaintainable messes unless the organization that builds them changes the way they create software.

Breaking the Circle

To break this circle the first step is that rewrites cannot be accepted by the development organization. This needs to be made clear by the development leadership of the organization.

Working with Legacy Code

Coaching the organization on working with poorly designed code without unit tests would be the first order of business. This is where Michael Feather’s book, Working Effectively with Legacy Code, can be used to teach techniques to improve poor code without unit tests while adding new functionality.

Refactoring

The next step would be to coach the team on refactoring techniques until they feel comfortable identifying code smells and refactoring to improve the code. It is vital to get the team’s commitment so that when problems in the code are encountered, they will be refactored. By the organization not accepting rewrites, the team will be put in situations where they have to improve these two skills.

Software Design Skills

Finally, the team will need to build the skills to create great designs. Teaching testable design techniques, test-driven development (TDD), and identifying design patterns and their appropriate use can all help improve the team’s design skills. Furthermore, ensuring that code reviews are taking place can also help arrive at quality designs. They are another fantastic mechanism for coaching developers.

Code Reviews

Creating good abstractions is hard. The joke that “the hardest part about software development is naming things.” is true. Giving something a good name is part of creating the appropriate abstraction in the code. Developers writing some new piece of functionality are authors; they’ve presumably had their heads in the problem for a while. Like every great writer needs an editor, great developers need editors too. In organizations with quality problems there are certainly problems with their code reviews, if they are even happening at all.

For teams to advance their software design skills, code reviews have to be happening at every level of the organization. There can’t be any rubber stamps based on seniority, title, etc. Developers who haven’t adopted code reviews as a common practice tend to view them as negative experiences. Comments on code reviews or rejected pull requests can be seen as negative criticism about the developer’s skills, and developers can take offense to them. It is important to identify this early and work with the team to make it known that code review comments and/or failed pull requests are the signs of a healthy development organization. Often times this fear of code reviews is an indicator of a larger problem with trust in the development organization.

Fix it Before it’s Too Late

It is important to figure out if your organization is stuck in this vicious software rewrite circle and to do all you can to help break free of it. This prevents the organization from ever achieving its potential. It will continue to operate inefficiently and release bug-ridden and brittle software into production. Furthermore, great developers will not thrive in environments like these, and will likely find work elsewhere.