The Importance of Static Code Analysis

30 Aug 2015 . development tools . Comments #code quality #static code analysis

Static code analysis is a critical tool for development teams who value code quality and continuous improvement. My most recent experience with static code analysis tools is with NDepend for .NET. So I will specifically discuss experiences I’ve had with that tool. However, a lot of the ideas in this article can apply to a majority of the static analysis tools that are currently available.

This is a follow-up to my previous post about Coding Conventions. If you have read that post you know that I describe how important coding conventions are to a development team. Once conventions have been documented the next step is to enforce them via a static analysis tool.

Rule Overload

One of the first things you will notice is that the majority of these tools come pre-configured with a set of static analysis rules. I recommend that you look at all of them closely. You may find that you are missing some critical rules and want to revise your team’s coding conventions accordingly. While I think this is a great idea, be mindful that the coding conventions should be short. So resist the urge to go back and add every rule into your coding conventions. Not all of the rules will provide the same benefit to your team. Some rules will not provide any benefit. You should focus on the rules that will provide the maximum benefit, and like everything else in software development, iterate on your static analysis configuration. NDepend in particular does a great job of providing a comprehensive set of critical and non-critical rules out of the box. But you will still want to modify them and create your own to match your team’s coding conventions.

Critical and Non-critical Rules

NDepend has the concept of critical and non-critical rules. Critical rules are ones, that if violated, will break your build. These should be reserved for your team’s coding conventions and other serious code quality offenders. The non-critical rules should still be enabled so that your team can continue to monitor them without failing the build. Non-critical breaches that continue to increase are a problem and you will want to address those accordingly.

This difference highlights two of the ways that you should be using the tool to get the maximum benefit for your team. The critical errors should fail the build immediately and require a developer change before there will be another successful build. The non-critical rules along with other metrics collected via your static analysis tool, cyclomatic complexity and coupling for example, shouldn’t necessarily fail the build but be part of a report that the team examines regularly. Armed with this information the team can focus their refactoring and clean-up efforts in a way that addresses the most problematic parts of the codebase first.

An Early Warning System

Bryan Helmkamp (founder and CEO of Code Climate) gave a fantastic talk at Baruco 2013, Building a Culture of Quality which I have referenced in previous posts. In his talk he describes that the natural trajectory for a software project’s quality is down. Because of this, we developers need to employ several techniques to prevent this from happening. One recommendation is to implement an early warning system. Part of your early warning system should be a static analysis tool.

There are several factors that can create environments where code quality suffers. These include schedule pressure, critical bugs that need to be fixed and deployed to production quickly, and changes in the development team members just to name a few. Furthermore, refactoring is a challenging skill to learn so teams may struggle to make the code better when adding features or fixing bugs. Even the best teams with agreed upon coding standards can suffer this fate. By putting developers who believe code quality is subjective, or have the “just get it done” attitude on teams who have no coding conventions you are creating a recipe for disaster.

This early warning system, your critical static analysis rules, is your safety net against code quality deteriorating over time. You will be notified as soon as you breach a critical rule, which is the optimal time to fix the issue. You can fix these issues as they arise as part of your daily development process. Otherwise, these issues will accumulate until they become a much bigger problem which will cost your organization a lot more time, money, and skill to reverse.

Overwhelmed by Legacy Code

If you are in a situation where you are working on a team that has ownership of a large amount of legacy code, static analysis tools will help focus your efforts to improve the code quality. Legacy code has several definitions. I start with Michael Feathers’:

To me, legacy code is simply code without tests.

— Michael Feathers, Working Effectively with Legacy Code

However, it is important to mention that often the lack of unit tests and code that is untestable go hand in hand. If there aren’t any unit tests or if the ones that do exist are terribly complicated, you can be fairly certain that the code under test is poorly designed and implemented.

You may find yourself in a situation where you now have ownership of a large amount of code that is tightly coupled, not cohesive, has no unit tests, contains large classes, the classes contain large methods, and there are a lot of static global classes and methods making it even harder to modify. And all of this code exists in the context of a larger system without an architecture where there are no boundaries or separation of concerns. This has happened to me more than once and it can be overwhelming. Being in these situations can quickly increase the team’s stress level and decrease the team’s morale as they feel like improving the quality is a impossible task.

It is in these situations that a static analysis tool can help your team determine a path to start chipping away at the worst code first. The tool can give you instant feedback as to the progress of your team and can start changing that stress and low morale into a feeling of accomplishment and forward progress.

The Boy Scout Rule & Opportunistic Refactoring

Some may think using a static analysis tool in this way works against the Boy Scout Rule (coined I believe by Uncle Bob Martin) or Opportunistic Refactoring techniques by Martin Fowler. Both of these techniques describe cleaning up the code you are currently working on. If you are not familiar with the Boy Scout Rule, Uncle Bob describes it as always checking in the code you are working on a little cleaner than you have found it. This is analogous to the Boy Scouts who leave the campground cleaner than they have found it. This same sentiment is echoed in Martin Fowler’s writing on Opportunistic Refactoring. Take the time to read his post about it if the concept is new to you.

Static analysis tools can be used in conjunction with these other refactoring techniques to optimize your approach to cleaning up the code. While still utilizing opportunistic refactoring techniques the type and extent of the refactorings can be determined by the static analysis rules that are currently being breached.

Metric Visualization

Static analysis tools use a variety of techniques to visualize metrics. These metric visualizations are a great place to start when trying to determine where to focus refactoring efforts when faced with a large amount of legacy code.

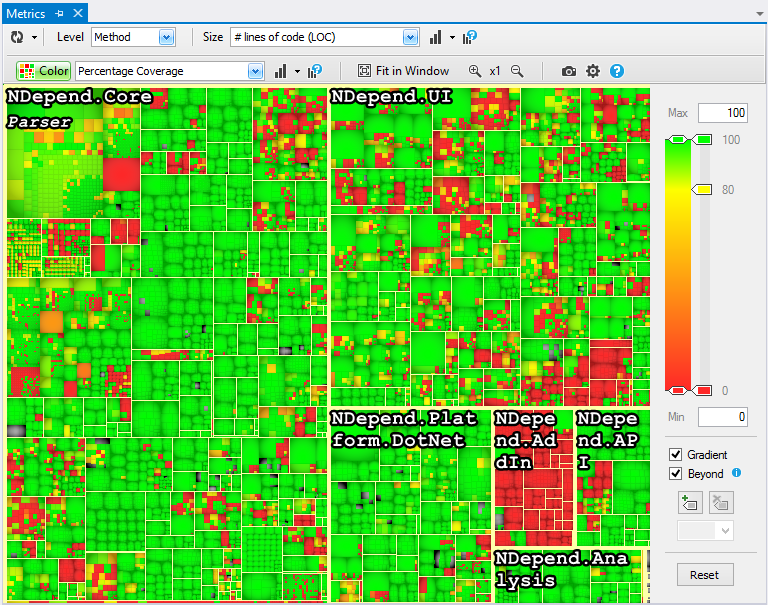

Treemaps in NDepend

NDepend uses treemaps to visualize metrics which I have found to be incredibly useful. A treemap is a visualization algorithm to display data via nested rectangles. These rectangles can represent various code elements in the system (including methods, namespaces, types, and a few others). The size of the rectangle represents one metric (e.g., method length or cyclomatic complexity). The color of the rectangle is used to represent a second metric like test coverage. This enables developers to correlate two metrics and use this information to determine refactoring techniques and priorities. You can read about treemaps in detail here.

Pressure to Ease the Rules

If you don’t have ownership of your entire codebase or you just took ownership of a large legacy codebase, you may need to relax the rules early in the process. While this isn’t ideal, you can use the concept of ratcheting to improve the software to the point where you can enable all of the critical rules.

Ratcheting

Ratcheting is a technique used to ensure that the overall codebase is getting better over time by introducing a practice gradually. Jez Humble describes the process in his book Continuous Delivery. In his example, he describes that early on in a practice’s adoption the build would not be configured to fail on a single rule breach. His examples include compiler warnings or TODO comments in the code. By employing a ratcheting technique, the software build would fail if the number of these breaches increased as compared to the previous build. If the development team is more aggressive about improving the software quality, the build could instead be configured to pass only if the number of these breaches decrease as compared to the previous build.

You can employ this same technique at a more granular level to determine if a specific rule should break the build or not. For example, you may have a rule that states a class can’t be more than 100 lines of code. If a legacy class is 300 lines of code and stays that size or gets smaller the rule can continue to pass. But if it becomes 301 lines of code, the rule will break the build. It’s also important to configure these rules so that all new classes will breach the rule if they are larger than 100 lines of code. NDepend’s CQLinq queries allow the creation of these regression type rules.

Don’t Go Backwards

Once you have rules in place you may feel the same kinds of pressure I’ve mentioned earlier which may encourage you to ease the rules. While it may feel like the “pragmatic” thing to do in the moment, I recommend that you fight this urge as you will lose your early warning system.

Conclusion

I will be writing more about static analysis tools and NDepend as I’m barely scratching the surface of the capabilities these tools provide. In the meantime give one of these tools a try on your team and you’ll see that there are significant benefits that can be gained by having detailed analysis of your codebase on every build.