Ping Pong Pair Programming

18 Apr 2015 . development practices . Comments #pair programming #tdd #unit testing

The most effective form of pair programming I’ve experienced is called Ping Pong Pair Programming. I find it so effective that I prefer not to pair at all if I cannot ping pong program. The majority of development teams I’ve encountered who occasionally pair program don’t practice ping pong pair programming. They view “pairing” as one developer taking a much more passive role. I suspect these teams would enjoy pair programming more and identify its benefits if they tried ping pong pairing.

I’ve read about Ping Pong Pair Programming as far back as 2002. However, I didn’t begin to practice it until I joined an eXtreme Programming (XP) team. I quickly took to the practice, finding it incredibly engaging and enjoyable. As someone who values collaborating with other developers this was collaboration at a level I had not previously experienced. Furthermore, this constant and close collaboration built a camaraderie with a team of developers which I have not been able to replicate since. There are about eight to ten developers with whom I’ve worked that I feel an incredible bond with as a result of constant pair programming over a significant period of time. These are folks I would jump at the chance to work with again.

Description

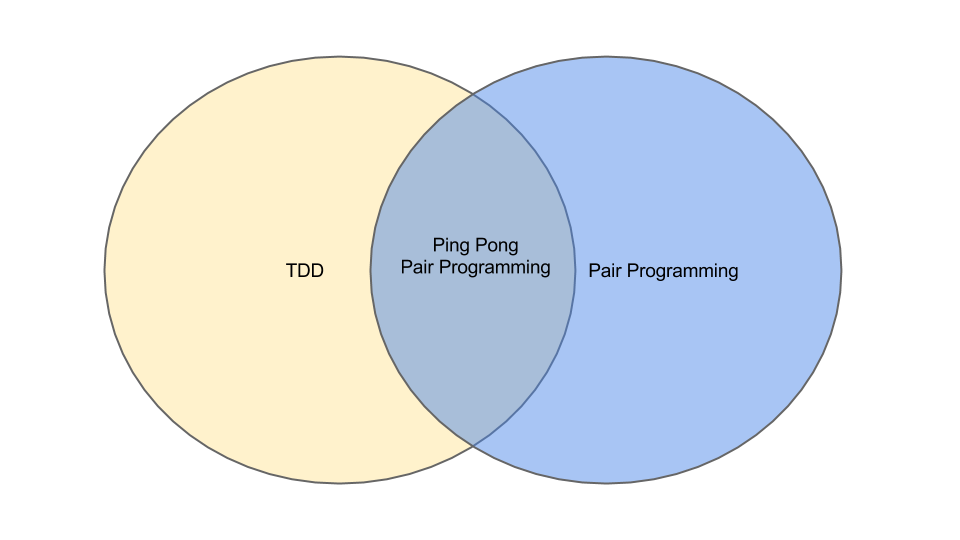

Ping Pong Pair Programming is the intersection of two XP practices:

- Test-Driven Development (TDD)

- Pair Programming

Ping pong pair programming is deceptively simple. Given two developers, Developer A and Developer B:

- Developer A writes a failing test

- Developer B makes the test pass writing only enough code to make it pass

- Developer B now writes the next test

- Developer A writes only enough code to make that test pass

- Continue until Developer A and Developer B both agree that there are no more tests for the unit they are currently working on

- Either developer can refactor the code only while all tests are passing

Computer Setup

One of the biggest struggles I see with development teams trying to pair program is that they don’t properly setup their development machines to accommodate this way of working. The optimal setup is a single computer with two input devices. That’s two monitors, two keyboards, and two mice. Frankly I won’t pair unless there are two input devices because I find it uncomfortable to work having to pass them back and forth between developers.

Physical Environment

Another very important aspect of pair programming is how the pair of developers are seated in relation to one other. The worst way to sit while pair programming is one developer in front of the other sharing the same monitor. Both developers need to be comfortably seated and able to take control of the computer at any point in the pairing process without any additional effort. The most common seating arrangement is two developers seated next to each other. While I don’t find this to be the optimal seating arrangement, it is usually the easiest in work environments that weren’t designed with pair programming in mind. I do however find myself resorting to it more often than I’d like to.

The ideal seating arrangement that I’ve found through experimenting with a previous team is sitting either directly or diagonally across from one another. This enables pairs to easily look at the screen and look directly at each other at all times during the pairing session (see the photo of one of our pairing workstations).

Benefits

Flow

I consider the biggest benefit of Ping Pong Pair Programming is how quickly the pair achieves flow. Flow is an important concept in programming. It is the point at which the problem space is completely loaded into the head of the developer and they begin making the most efficient progress on the solution. Any interruption at this point sets the developer back.

When practicing TDD and pair programming a much smaller problem space needs to be managed to begin making progress on a solution. This enables developers to get into flow quicker than other programming styles where the entire application’s problem space needs to be known. Working in this way, a distraction is much less damaging to the progress of the pair.

Avoids Mismatched Pair Issues

In a pair there is typically one developer who knows more than the other either about the domain, the problem currently being addressed, the technology stack, or even programming in general. This mismatch could lead to poor pair programming sessions with the more experienced programmer dominating the keyboard.

These mismatches can cause developers to feel like they are providing very little input and they tend to get bored and disengaged from the work. While more experienced developers can feel like they are doing all of the heavy lifting. It is no surprise that these developers eventually decide pair programming is not for them.

Ping Pong Pair Programming avoids these issues as each developer is taking turns writing tests and making them pass. If the developer is unclear about what test to write next or how to make a specific test pass this prompts a conversation.

Learning & Mentoring

Given that conversations are constantly happening in the pairing session this is a very natural way to incorporate mentoring into your team. This type of mentoring is more effective than mentoring sessions between developers and managers in private one-on-one meetings. Don’t get me wrong, you should be having one-on-one meetings with your manager, but the real mentoring should be happening while building the software. By pair programming, mentoring is something that is occurring constantly and naturally between developers of different skill levels. Additionally, learning new techniques, 3rd party libraries, tools, team practices, team coding conventions, etc. becomes very easy and built-in to the pairing process.

Some teams will even stop performing code reviews and allow the review to happen during the pairing session. I believe this is entirely dependent on how often your team switches pairs. If one pair commits to a user story and only finishes pairing when the story is complete I think that code should be reviewed. As Bryan Helmkamp stated in his Baruco 2013 talk both developers in a pair are the authors, therefore they still require an editor. However, if many developers on the team have worked on the user story through regular pair rotation the code review becomes redundant.

Teaching Test-Driven Development

I am a huge advocate of TDD. I have had a lot of success with it and I have yet to find a situation in which I do not want to utilize it. Test-Driven development, while conceptually simple, takes a fair amount of time for developers to get truly comfortable with. There are some common struggles that developers new to TDD experience. These include:

- Not doing the simplest thing to make a test pass

- Taking too big of a step

- Writing integration tests instead of unit tests

Even the act of just writing the test first is something that is a challenge for developers who haven’t worked that way previously. All too often “unit tests” that inexperienced developers write are impossible to maintain, impossible to reason about, and end up being an opposing force instead of an enabling force in the organization. These are situations where teams give up on unit testing and decide “it didn’t work for us.” See one of my previous posts for more on this topic, xUnit is Not Unit Testing.

Being introduced to TDD in a ping pong pair programming situation is the fastest way for a developer to get up to speed and comfortable with the practice.

Pairing with a seasoned TDD practitioner, developers new to the practice will learn:

- How to avoid external dependencies (database access, file system access, external services) that slow down unit tests.

- The recommended scope and size of a unit test.

- How to make unit tests as clear as possible so they can be an excellent documenting technique.

- How to write testable code and begin to recognize the bad programming habits that they have accumulated over time that make unit testing their code impossible.

The fact remains: Good design is testable, and design that isn't testable is bad.

— Michael C. Feathers, Working Effectively with Legacy Code

The Game

As developers become better at Ping Pong Pair Programming it can begin to look like a game (hence the name Ping Pong Pair Programming). A developer will do the minimum to make a test pass including hardcoding an expected result if there isn’t a test to prevent them from doing so. If a developer writes a test to exercise a conditional statement but only one branch of the conditional statement is currently tested, the implementer will not add the conditional statement. Two tests would be required to test both branches of the condition and therefore shouldn’t be implemented until both tests exist.

From the perspective of the uninitiated developer this can seem silly or wasteful. If you know how the code is supposed to look why wouldn’t you write it that way in the first place? But what looks like a game from the outside is a very important part of TDD and pair programming. It is doing the absolute minimum to make a test pass and no more without another failing test.

Pair Rotation

When I first started Ping Pong Pair Programming we switched pairs on the team twice per day (two four hour sessions). In the early days of XP teams tended to keep the same pairs throughout an iteration. Switching pairs regularly has several benefits over keeping pairs together for the duration of an iteration. It alleviates the need for code reviews (as mentioned previously) and it spreads knowledge throughout the team very quickly. In my experience, every developer on the team paired with one another, thus there were no “favored pairs.” Very rarely would a user story be completed in a single pairing session, this resulted in a true team-owned solution and team accountability for the success of every user story.

Promiscuous Pairing

Promiscuous Pairing recommends switching pairs even more rapidly (e.g., I’ve read about teams switching pairs every 90 minutes). If you’ve never heard of Promiscuous Pairing you can read about it in Arlo Belshee’s article.

Conclusion

Like everything in software development, Ping Pong Pair Programming is no silver bullet. There are times when pair programming may not make sense based on the task, the team personalities, etc. But I would strongly encourage you to try Ping Pong Pairing before deciding that pair programming is not for you.

Credit

Thanks to my friend and colleague Nick Goede for the photo of our pairing workstations from his Barcamp Philly presentation.