The Appropriate Size for a Test

11 Oct 2014 . software craft . Comments #unit testing #tdd #code quality

Recently at work I showed a video of Gerard Meszaros’ talk from CRAFT Conference 2014, Find the Right Abstraction Level for Your Tests during one of our lunch and learn sessions. The audience was our development team with varying experience writing tests. A few of us had a lot of experience writing tests and practicing TDD, a majority had some experience writing tests but don’t practice it regularly, and there were a few, I’m sure, who haven’t written a unit test or an automated test before.

During the discussion that followed the video a team member mentioned that the talk didn’t address what the appropriate size for a test was. I thought that was a great question for a team that previously didn’t have much success with their unit tests.

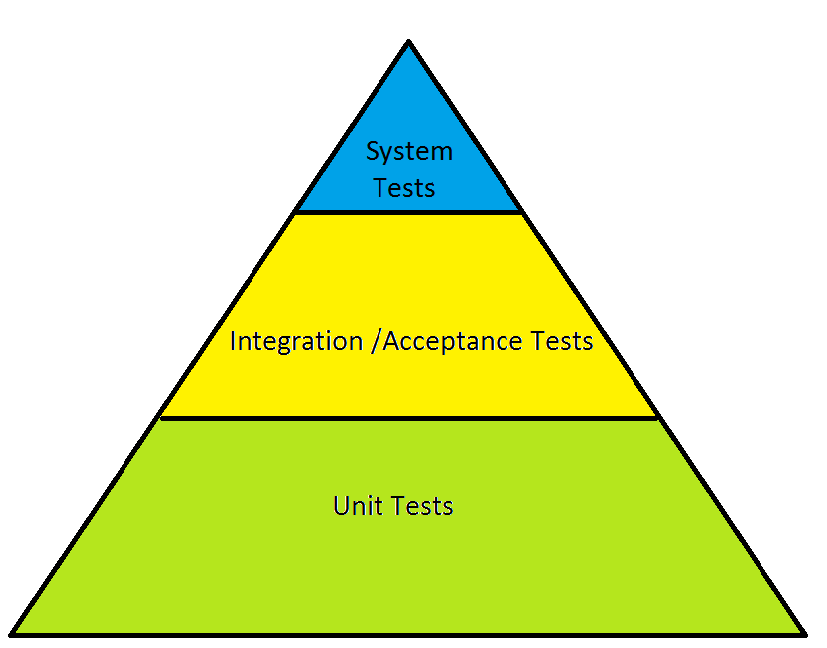

If you recall from the video Gerard uses Mike Cohn’s test automation pyramid as one of the diagrams that are central to his talk. The pyramid shows a lot of small unit tests (which should have a small scope but a lot of detail). As you move up the pyramid you get to Integration or Acceptance tests which have a medium scope and medium level of detail. And finally you get to the top of the pyramid and get to system level tests (sometimes represented as UI-driven tests in some versions of the test automation pyramid I’ve seen) which should have the broadest scope but be very light on detail. There should be a lot less of these.

If you recall from the video Gerard uses Mike Cohn’s test automation pyramid as one of the diagrams that are central to his talk. The pyramid shows a lot of small unit tests (which should have a small scope but a lot of detail). As you move up the pyramid you get to Integration or Acceptance tests which have a medium scope and medium level of detail. And finally you get to the top of the pyramid and get to system level tests (sometimes represented as UI-driven tests in some versions of the test automation pyramid I’ve seen) which should have the broadest scope but be very light on detail. There should be a lot less of these.

So, I took the original question and extended it to discuss when you know you’ve crossed a boundary on the testing pyramid.

Unit Tests

There is no concrete rule for the size of a unit test obviously, but there are some heuristics people use when writing unit tests. A couple of them are that a unit test shouldn’t exceed a dozen or so lines and a unit test shouldn’t take more than a minute to write. Unit tests are supposed to be as short as possible. The rationale is that if you are writing unit tests to cover all of your system logic (as you would if you were practicing TDD) they should be very simple to understand and to update so that there is a negligible cost associated with creating them and maintaining them. This is one of the reasons why teams who practice TDD don’t ever consider the “cost of writing a unit test.” Because the cost is minimal compared to the benefits of having a small, easily understood test to verify some functionality.

One of the biggest benefits is that unit testing encourages better software design. Implementing smaller objects, smaller methods (with smaller numbers of parameters) and a decoupled design makes it possible to write small tests.

An indicator that you are no longer writing a unit test is the amount of setup a test requires. A unit test should require a very minimal setup. Also it should not rely on external dependencies. Unit tests shouldn’t hit the database, read from the file system, or call external services. These tests should be optimized for speed so there is no reason for developers not to run them constantly.

Integration / System Tests

I believe the difference between these two types is less important than knowing when you are no longer writing a unit test. This is a very common issue as it is often referenced as one of the beginner unit testing and TDD pitfalls: The over-reliance on integration tests. Once your unit tests are free of integration and system level tests you can begin to focus on the difference between those tests and making sure you have the appropriate amount of those.

However, there were a few rules of thumb in Gerard’s talk. An “integration” test is a single use case where a “system” test is a multi-actor test case that exercises more than a single use case. Some consider UI-driven tests the top of the pyramid. The important take away, I believe, is that as the amount of setup increases the number of those tests should decrease because they become harder to maintain and become more brittle. As opposed to unit tests Integration and System tests could hit the database and rely on external dependencies.

While unit tests should be as small as possible, integration and system level tests will, by their nature, be longer and require more setup. These tests are testing more of the system and sometimes require external dependencies to be configured and setup. Additionally, if you are using a UI testing framework or an acceptance test framework like FitNesse for your tests the additional adapter code to bind the test fixtures to the software under test makes tests more brittle.

Something that wasn’t discussed in the video is that the unit tests should be able to be isolated from the system and integration tests. The reason is that unit tests should be run constantly (or on every commit at a minimum) whereas the system and integration tests (which take longer to run) should only run on the build server or in another testing environment.